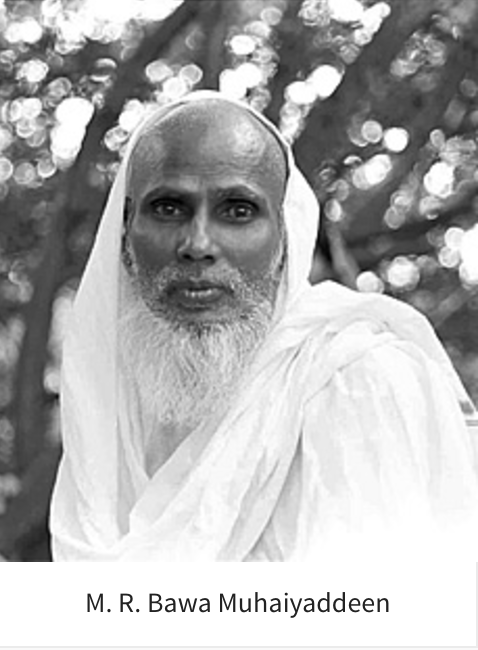

In October 1971, Muhammad Raheem Bawa Muhaiyaddeen (d. 1986) was welcomed by a handful of spiritually interested American followers at the Philadelphia International Airport. Little did they know at the time that they were meeting a spiritual teacher who would go on to be one of the formative teachers in the North American spiritual and religious landscape, especially in terms of disseminating Sufism to an American, and subsequently to a global, audience.

“The development of Sufism in North America is a rather complex one. The intricacy is due in part to the reality that Sufism as a mystical and spiritual tradition within Islam did not develop homogeneously, but rather transformed as it was transmitted beyond the Arabian Peninsula from its inception to the present period.”

Sufism and Islam

The development of Sufism in North America is a rather complex one. The intricacy is due in part to the reality that Sufism as a mystical and spiritual tradition within Islam did not develop homogeneously, but rather transformed as it was transmitted beyond the Arabian Peninsula from its inception to the present period. At the same time, Sufism’s relationship with Islam has also shifted throughout its development within Islamic and non-Islamic contexts. In its early stages, the movement attracted females and males who subverted and critiqued societal and Islamic norms through radical austerity, while during the height of Islamic empires, such as the Ottomans and the Mughals, Sufi figures and spaces were given patronage by leading political figures, enabling Sufism to become mainstream Islam. However, this position of centrality and privilege shifted with the fall of Islamic empires and the onslaught of colonialism. Here again, varying Sufis maintained complicated positionalities with colonial powers. Some, for instance, were the conduits for colonial administration of the local population. Examples of the latter was evident in South Asia, where alliances with shrine administrators was important for colonial control. On the other hand, however, figures like Abdul Qadir al’Jaziri (d. 1883) actively mobilized against colonial oppression by the French in Algeria.

In the midst of these complex imperial dynamics, one of the significant realities of colonialism was the encounter of the literary tradition of Sufism by non-Muslims (i.e., Europeans). It should be said that this was by no means the first time that non-Muslim westerners encountered Sufism. One can note the exchanges that unfolded between European traders in the Ottoman empire and Sufis, which produced numerous paintings and travelogues. The examination of these paintings and travelogues showcase some of the early instances of the exoticization of the Mevlevi Sufi tariqa’s (order) meditative tradition of whirling. Additionally, during this colonial period, there began a systematic relationship with Sufi poetry by European Orientalists, who were for instance studying Arabic in Cairo, Egypt (Edward Lane d. 1876) or Persian and Sanskrit in India (Sir William Jones d. 1794). These figures began to translate some Sufi poetry which made its way back to an European audience, which in turn influenced intellectual and literary movements, such as Romanticism.

“…varying Sufis maintained complicated positionalities with colonial powers. Some, for instance, were the conduits for colonial administration of the local population. Examples of the latter was evident in South Asia, where alliances with shrine administrators was important for colonial control. On the other hand, however, figures like Abdul Qadir al’Jaziri (d. 1883) actively mobilized against colonial oppression by the French in Algeria.”

These poetic transmissions began the process wherein Sufism as a tradition was compartmentalized and differing elements of the tradition was valued inconsistently. For instance, whereas the poetic traditions of Hafiz (d. 1390) or Rumi (d. 1273) were treasured, they were juxtaposed against living Sufism, which was seen as popular, superstitious, and, at times, backwards. Living Sufism was essentialized for its mendicancy and asceticism, while its ritual and spatial practices was understood as appealing to the masses. These framing of Sufisms in effect created polarizing representations of the tradition and its relationship with Islam. The latter bifurcated treatment of Sufism in the non-Muslim world was unfolding just as Sufism in the Muslim world was also experiencing oscillations, especially at the hands of some reformist groups who viewed Sufi practices as cultural stains and theological heresies in Islam, which led to the further development of anti-Sufi programs in some Muslim majority countries. It is within this broader complex global landscape that contemporary Sufism must be understood, such as the development of Sufism in America.

Sufism in America

In many ways, it was because of the poetic traditions which made its way across the Atlantic Ocean into America that set the scene for the reception of Sufi teachers in America. The first known Sufi teacher to arrive was Hazrat Inyat Khan (d. 1927). He sailed to New York in 1910 from Bombay, India with his musical troupe. The reception of Khan to America was impacted by numerous spiritual and esoteric movements. The Theosophical Society had formalized its forays into esoteric and philosophical traditions of the spiritual East, while figures in the Transcendentalist movement, such as Ralph Waldo Emerson (d. 1882), were well-steeped in the poetry of Hafiz and Rumi. Thus, Khan’s presentation of Sufism was very much defined by this spiritual landscape. He did not frame Sufism purely in Islamic terms, though that was indeed the context from which he came from. Rather, he spoke of it through the language of universalism, which appealed to his spiritually curious American Christian audience.

The further institutionalization of Sufism, though, would take a few more decades to unfold and this process was especially defined by another significant cultural period in America, that of the counter-cultural movements of the 1960s and 1970s. The era of civil rights, first wave of feminism, and protests against foreign wars (i.e., Vietnam War) resulted in another religious and spiritual turn for an American audience who were anti-establishment. One development of this counter-movement was the shift once again to look to the exotic East for perennial truths. In effect, leading to the proliferation of Hinduism and Buddhism, and other esoteric traditions in America, of which Sufism was only one thread.

“Bawa’s arrival in Philadelphia was motivated by several factors. Firstly, one of his Muslim Sri Lankan students, Mohamed Mauroof, who was residing in Philadelphia at the time, felt that Bawa would be a welcome voice to addressing the racial issues in Philadelphia, especially as a result of the assassination of prolific civil rights voices, such as Martin Luther King Jr (d. 1968) and Malcolm X (d. 1965).”It is during this time that Sufi teachers arrived from different countries such as Bosnia, Turkey, and Sri Lanka to America to disseminate Sufism to an American non-Muslim audience. Each teacher established their own traditions, lineages, and practices, some affirmed their relationship to Islam, while others framed their teachings in more universal languages that did not include ritual practices found in Islam. The ways in which Sufism was framed for the American audience, particularly in terms of Sufism’s relationship to Islam ritually, such as the performance of salat (five times a day ritual prayer) and/or fasting (during Ramadan), was and is a process for many of these Sufi communities and dependent mostly on the discretion of the leader of the community. As such, in approaching these different communities in the American context today, each of these teachers and movements need to be assessed and understood within their own context to truly appreciate the complexities of the movements and its adherents. This then brings us to one formative teacher and his movement in America, Bawa and the Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship (BMF).

Bawa and the Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship

It is in this context that Muhammad Raheem Bawa Muhaiyaddeen (henceforth will be referred to as Bawa) arrived to Philadelphia, which Chapter 1 of my book, Sacred Spaces and Transnational Networks in American Sufism:Bawa Muhaiyaddeen and Contemporary Shrine Cultures, situates. His first movement institutionalized in Sri Lanka as the Serendib Sufi Study Circle, but he also led a parallel American movement known as the Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship (BMF). He tended to both his Sri Lankan and American communities until his death, but below I will focus primarily on his American movement.

Bawa’s arrival in Philadelphia was motivated by several factors. Firstly, one of his Muslim Sri Lankan students, Mohamed Mauroof, who was residing in Philadelphia at the time, felt that Bawa would be a welcome voice to addressing the racial issues in Philadelphia, especially as a result of the assassination of prolific civil rights voices, such as Martin Luther King Jr (d. 1968) and Malcolm X (d. 1965). At the same time, another female American student was writing letters to Bawa asking for spiritual guidance but was financially unable to visit Bawa in Sri Lanka. As such, both of them mobilized with a local yoga group in Philadelphia and made the preparations for Bawa’s arrival by forming the Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship.

After his arrival, Bawa began discoursing or hosting public lectures. In this early stage, Bawa began to attract many members of Philadelphia’s African American Muslim communities, such as members of the Moorish Science Temple (MST). Overtime, however, the demographics of the group shifted to include members from a predominant European American (white) background. At the time, some African American members did not feel comfortable with the growing racial and socio-economic differences in the BMF. Despite Bawa’s attempts to teach his students to transcend social labels of race, class, caste, and gender and focus on the oneness of God, many early African American members of this movement left, but a few stayed on as seminal leaders and members of the BMF and still remain as such today.

Living Sufism at the Tomb of Bawa Muhaiyaddeen

In Chapter 3, I highlight how the demographics of this community changed once again after the death of Bawa in 1986, especially as he appointed no successor to his movement in America or Sri Lanka. When Bawa died, he was initially buried at the Fellowship farm in Coatesville, about one hour outside of Philadelphia. Originally, Bawa’s grave had a very simple fence as its marker, but eventually his senior students decided that they wanted to memorialize their teacher, which led to the building of a shrine over his tomb. The design was formulated by Michael Green, an American Sufi artist and student of Bawa, but was built by the members of the BMF. In so doing, this mainly American-Sufi members of the Fellowship unknowingly built a shrine that held much capital in the Muslim world but was novel to its American milieu.

“In Chapter 3, I highlight how the demographics of this community changed once again after the death of Bawa in 1986, especially as he appointed no successor to his movement in America or Sri Lanka. When Bawa died, he was initially buried at the Fellowship farm in Coatesville, about one hour outside of Philadelphia…”

Slowly, diasporic Muslims from the east coast of the United States began to trickle to the farm and mazar space in Amish country in Pennsylvania. Through word of mouth, newspaper advertisements in local communities (such as Pakistani newspapers in NYC etc.) and through social media (especially Facebook), the news spread that there was a South Asian Sufi teacher entombed in Pennsylvania and his grace was ever present. Diasporic Muslims, a majority of whom are South Asian and Middle Eastern Americans, marveled at the accessibility offered by this sacred space. A space that they were familiar with in their natal homelands of Pakistan or Iran, which they could now utilize in America. With Bawa’s death, it is this site that has become a formative space both for the institutional members of this community, but also for non-Fellowship members who are Muslims seeking to access blessings (baraka) of a Sufi saint (awliya). It is here that one sees the vibrant complexities and coexistences of Sufism in America. Chapter 3 captures some of these narratives through the voices of pilgrims and disciples at the tomb of Bawa. I will share two examples here.

Slowly, diasporic Muslims from the east coast of the United States began to trickle to the farm and mazar space in Amish country in Pennsylvania. Through word of mouth, newspaper advertisements in local communities (such as Pakistani newspapers in NYC etc.) and through social media (especially Facebook), the news spread that there was a South Asian Sufi teacher entombed in Pennsylvania and his grace was ever present. Diasporic Muslims, a majority of whom are South Asian and Middle Eastern Americans, marveled at the accessibility offered by this sacred space. A space that they were familiar with in their natal homelands of Pakistan or Iran, which they could now utilize in America. With Bawa’s death, it is this site that has become a formative space both for the institutional members of this community, but also for non-Fellowship members who are Muslims seeking to access blessings (baraka) of a Sufi saint (awliya). It is here that one sees the vibrant complexities and coexistences of Sufism in America. Chapter 3 captures some of these narratives through the voices of pilgrims and disciples at the tomb of Bawa. I will share two examples here.

A Sufi Mazar in Coatesville, PA

Though the branch in Coatesville is understood mainly as the mazar, for members who live near it, it is actually their farming community. Some members of the Fellowship moved close to Bawa’s grave after his death. They are the caretakers and hosts to the many visitors and pilgrims who arrive at Bawa’s tomb. It was not a task they were expecting to perform, but it is one that has emerged due to the popularity of the visitors. The property is over 100 acres now, and consists of a farm, which the community tends to as Bawa himself was a farmer, along with a community center, prayer pavilion, and cemetery. They hope that in the future they will become a fully self-sustainable farming community. The members of this branch of the Fellowship host weekly meetings on Sunday mornings, where they listen to recorded discourses given by Bawa. The cemetery is exclusively for members of the Fellowship who are buried according to Islamic burial practices, as taught by Bawa. These American Sufis, who are both Muslim and non-Muslim, are now hosts to the growing diasporic Muslim pilgrims, but their volunteer work at the farm represents the dedication they have for their deceased teacher, whom they still to serve.

During one of my visits to the Fellowship mazar and farm in April 2013, I met a group of male Pakistani-American pilgrims from New Jersey. They informed me that they had heard about the tomb of Bawa through community members and through social media, but they did not believe that the mazar was real. So, they got in their car and drove from New York State to Coatesville to see it with their own eyes. Once they arrived, they were overwhelmed. Immediately they relayed that spaces like this exist in Pakistan, where they are from, but the idea of finding a similar space here in America was a blessing. In entering the shrine, they conveyed that they “felt [as if they were] back home.” Now, they no longer have to travel to their natal lands to experience the graces of a Sufi teacher. They can make the same pilgrimage (ziyara) in America. The development of ziyara to Bawa’s tomb has meant that busloads of pilgrims arrive at the mazar regularly, especially during the summer.

“The property is over 100 acres now, and consists of a farm, which the community tends to as Bawa himself was a farmer, along with a community center, prayer pavilion, and cemetery.”

In Chapter 3 and the conclusion of my book I highlight that the differing experiences of the pilgrims and members of the Fellowship at the shrine, especially their ritual performances and movements in and around the shrine, has led to some moments of tension and negotiations. New groups of pilgrims bring their cultural practices to the tomb of Bawa. Practices such as holding picnics outside the shrine, or even singing, lighting incense, and offering foods to Bawa, has alarmed some American caretakers, who want to maintain the shrine as a space for silent meditation and reflection on Bawa’s teachings, and not solely about accessing his blessings. Now, signs placed by the caretakers, can be found around the property asking visitors to honor the silence of the space, while also barring lighting of incense or spreading rose water. The processes that are unfolding between American practitioners of Sufism and diasporic Muslims at the shrine brings us to the negotiations found within Sufism, especially spatially but also theologically, that have unfolded in historical context and have continued into America.

Conclusion

Sufism as a tradition has meant many things across space and time; it has been and is a literary and poetic movement, at the same time that it has been fundamentally shaped by Islamic philosophy, in the form of Neo-Platonism, theology (kalam), and fiqh (law). It has also been profoundly shaped by numerous local cultural realities as Islam expanded geographically, be it in South Asia, Southeast Asia, Central Asia, and North Africa, and, now America and Europe. In its embodied forms, Sufism meant accessibility to the grace of God (baraka) at the feet of holy figures, be they dead or living. It also endorsed a deep contemplative and introspective turn in the experience of God, the prophets, and his saints (awliya) through the denial of the world and also through the world. Politically, it was given patronage by caliphs, or has been invoked by the socially marginalized, especially women and/or those with gender-fluid identities. Yet, several of these practices, or even all of them, have been deemed heretical by some Muslims who claim a literal and exclusive orthodoxy, which has at times led to virulent attacks against Sufis and their spaces (especially shrines). This expansive diversity is often at times neglected when we approach the study of Sufism, not only in Muslim majority countries, but also in European and American ones too.

“The case study of Bawa, and the Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship, bring to the forefront these perennial complexities. Not only of the relationship of Sufism to Islam, but also of the nature of Sufism itself, while introducing new realities, especially the role that Sufism plays for diasporic Muslims contending with displacement and immigration through memory and space.”

The case study of Bawa, and the Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship, bring to the forefront these perennial complexities. Not only of the relationship of Sufism to Islam, but also of the nature of Sufism itself, while introducing new realities, especially the role that Sufism plays for diasporic Muslims contending with displacement and immigration through memory and space. It is these stories, along with the Sri Lankan narrative, which I have not touched upon here at all, that I introduce and complicate in my study of the transnational movements of Bawa. I do this with the hope that such an approach will help us to think more seriously about American Sufism and the ways in which it is connected to broader global Sufism, while also challenging Religious Studies scholars to think more fluidly about religion in its everyday embodied forms.

* Top image is taken from the official web page of Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship, www.bmf.org.

* Other images belong to the author, Merin Shobhana Xavier.