[Ahmet Köroğlu] First off, how about we get to know you briefly?

[Namık Sinan Turan] I was born in Tarabya, Istanbul in 1972. My entire life of learning happened in Istanbul. After studying Political Science and International Relations at Istanbul University, I completed the work for my master’s degree in 1998 in the same division’s Political History Department. Afterwards, I gave a doctoral dissertation in 2003 entitled Structural Change in the Caliphate and the Ottomans. My studies focus on the much later Ottoman period and the social and political history of the Second Constitutional Period. My work areas constitute Ottoman diplomacy, political thought, and culture. My latest book, The Caliphate: From the History of Early Islam to the Last Century of the Ottoman Empire, came out of Istanbul Bilgi University publications in May 2017. I am currently continuing my studies in the Department of Political Science and International Relations at Istanbul University’s Faculty of Economics.

Do music and Umm Kulthum have such a distinct importance in your academic studies? What led you to Umm Kulthum?

I examined the transformations that socio-cultural change had had on music in Turkey while preparing my master’s thesis. At that time, working on these issues in the field of politics was not very common. The reason could also have even been some prejudices. Nowadays, however, studies on the social and political aspects of music can now be examined with a more interdisciplinary view. In the following period, my studies continued on the relationship of music and culture. While working on the Middle East in particular, I was able to see more widely the role of music and literature among the symbols produced there. From here I did studies investigating the relationship of music and the cultural identity of the Middle East through the examples of Egypt and Lebanon in connection with Umm Kulthum and Fairuz.

I would like to first start with music. But it is as if the general opinion is the opposite, as if music has an important function that has mobilized society in the Middle East; do you agree with this?

Of course it has an important function. If we look more generally, it has a more privileged position in transferring music culture, in establishing relations among societies, and above all in forming identity compared to the other arts. Friedrich Nietzsche and Arthur Schopenhauer defined music as a strong/effective force that motivates people more than any other art. While the shocking effects of the ideology of nationalism in the 19th century were not just being felt in Europe but also in the Balkans and the Middle East, literature, theater works, and in particular music transformed into the integral tools of a cultural identity project. In the same century, music was not just being performed; it was also being analyzed and included in the academic debate on culture. Since the beginning of the 20th century when the construction of nations and the phenomenon of modernization accelerated, music has accompanied the process of social and political fractures. In countries of the Fertile Crescent, particularly Egypt and Syria, music saw the incumbency of a social mortar. It passed common feelings, pains, defeats and victories, traumatic civil wars, and of course the hundreds of years of rich literary culture and audio memory, as well as playing a big role in staying alive. Many names, both as performers and composers, have thus contributed to the music production process.

On this point, if we come to Umm Kulthum, mustn’t she also have been an important contributor in this musical adventure…especially if we are talking about the Middle East?

On this point, if we come to Umm Kulthum, mustn’t she also have been an important contributor in this musical adventure…especially if we are talking about the Middle East?

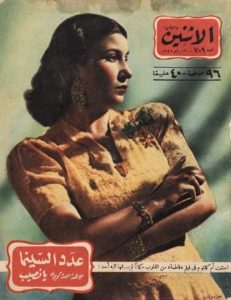

We can see Umm Kulthum as being also perhaps the most appropriate name that can assume this qualification. In other words, reading the complicated and oh-so striking relationship between music culture and social structures in the Middle East is possible through Umm Kulthum’s career. In Tournier’s words, Umm Kulthum transformed the soul of Egypt and Arab societies in a geography that had experienced chaotic developments at the beginning of the 20th century. Aside from being the most important representative in music, the presence of the cultural Al-Nahda and the dream of the national ideal and Arab nation meeting under a common roof became a legendary bond established with the past for the Arab world. Through her great talent, which had a personal story beginning in mediocrity similar to the stories of other Middle Eastern women, her musical mastery, and her attitude toward shocking social developments, her tone was a common one that brought Arab society together in the modern century. For Egypt and the Arab nation, Umm Kulthum was a “common tone that united the imaginary community,” as was in the determination of Benedict Anderson in his work that provided a significant contribution to the theories of nationalism.

Everyone is also a product of the age in which they live. In this sense, the social conditions found both in time and space and within are found reflected in your studies. Before moving on to Umm Kulthum’s musical direction, what were the socio-political conditions of Egypt that brought Umm Kulthum into being?

Yes, as you have also emphasized, Umm Kulthum’s life had accompanied the most significant fractures of modern Egypt and even been shaped in the light of these developments. Egypt did not just stay as the center of intelligence; it was the one place where modern art took its first steps in the Arab world. Its charm drew playwrights and actors there like Salim al-Nakkash, Suleyman el-Kardawi, and Suleyman el-Haddad. Yaqub Sanu initiated a new theater movement in Cairo. Following his education in Europe, he came out before the audience with a repertoire composed mostly of operettas and light comedies. At a time when he lost his influence, the weightiness of the playwright, Ahmad Fahim al-Far, was felt this time. The language and exaggerated acting of the Lebanese Jurj Abyad, who led an immigrant life in Egypt, only addressed the upper class. The Egyptian ruling class and the elite with their lifestyles that the English also brought after 1882 were not having problems adapting Western cultural institutions. Just the opposite, they used the elements of a Western way of life as the symbol representing Egypt’s level of development. Alexandria became a privileged port city that was connected with the capitalist world economic system. The city’s physical structure and appearance reflected a very Western atmosphere. Alongside this, tradition and the modern were represented side by side in Cairo. The viceroy Isma’il Pasha ordered an opera from Giuseppe Verdi to be presented at the opening ceremony of the Suez Canal, which was to be quite splendid, and built an opera house in Cairo for exhibiting this. The opera house, which had a Western polish to Cairo’s traditional skyline, was also the symbol of Cairo’s multicultural identity. Neither was this posturing of Viceroy Isma’il at first a deliberate act for the Eastern monarchs of the period, including the Ottoman Sultans.

Egypt of course also has political conditions, in particular the British colonial period, which would have an important role in the formation of nationalism. Mustn’t these also have been important steps?

The British of course were a decisive historical factor in this sense. This British occupation formed an important groundwork in creating the feelings that brought about Umm Kulthum and what she addressed. When comparing the British occupational forces with the Egyptian population, even though these units were small, they reminded the Egyptians of Britain’s strength in the region. Although the Egyptian army had not been demobilized, it had been quite downsized, and command level had been given to the British. The British reinforced their control over Egypt through local administrations. During the occupation period, Britain implemented policies modeling their experiences in India. The Egyptians were the heads of the policies that they watched being held from afar, aware of the industrial structure that had become the tool of the British colonial system and the forcefulness of the British class in public and administrative affairs. However, the British were able to achieve only partial success in this regard. By organizing the dissident intellectuals in Egypt, the first modern nationalist parties were formed in the Arab world. The presence of the imperialists in the country was also the cause for the birth of nationalism in Egypt, just as in Algeria. The British, based on the actions of the viceroys that preceded them, engaged the Egyptians in activities within a common market. This situation inspired the feeling that created a national community among the people of Egypt. Additionally, the presence of the British in Egypt provided a clear goal that would be able to be mobilized in the face of the Egyptian public. As Gelvin points out, this is why the Egyptian national movement followed a different trajectory than the nationalist movements in the rest of the Ottoman lands. Over time, this difference provided the birth of the Egyptian identity as the identity of a separate country and the widespread myth that led the origin of this identity as far back as the antique age. The mainstream nationalist movement in Egypt in the years following World War I did not favor a radical social transformation. Already this movement represented the interests of two classes who were extremely fearful of a democratic administration and social revolution and of the intellectuals who had experienced vertical social mobilization with the large land owners. Neither of the two groups rejected Europe or European ideas, and the understanding of nationalism clearly showed how much the worldviews of the European-type nation and state had taken shape.

I guess all these changes also showed themselves in the social and art life. Where did the trends in Egypt in this period point to; for example, poetry, theater, music, etc.?

City life, individual preferences, and consumption patterns also changed while Western civilization took the Arab world under its influence through colonial and non-colonial traces. Restaurants, cafes, and cinemas provided new entertainment styles and meeting places; women were able to go out freely, and those who had been educated younger could get involved in the public area without a veil or with little covering. Home life was more relaxed. Anymore, men and women were not just experiencing a single neighborhood; they were traveling long distances to get to work, and the extended family was able to spread out to the whole city.

“The first gramophone records of Arab music were made in Egypt in the early 20th century. The demand seen for radio broadcasts and musical films led to changes in the tradition of music. Musical films were being transformed from improvisations to written and rehearsed presentations.”As Albert Hourani pointed out, technological developments did not stick with spreading the new relationship models coming from the West to wider areas, they were also brought to a deeper level. The tools of the new mass media created a universal discourse that united more integrally than the travels that the educated Arab pilgrims and scholars had done. Newspapers published in Cairo were also being read outside of Egypt. In this period, poetry, novels, popular science, and historical works were being produced everywhere that Arabic was read. In 1914, there were cinemas in Cairo and other cities; in 1925, the first original Egyptian film was made based on Zeynep, the first original Egyptian novel. By 1939, Egyptian films were being shown in the entire Arab world. Meanwhile, there were local radio stations broadcasting conversations, music, and news. Travel, education, and the new mass media helped create a world of common pleasures and ideas. The European example and new mass media also opened the way to changes in the forms of artistic expression. All visual arts were in a phase between the old and the new. Painters and sculptors had begun working in the Western style, even if they didn’t have much impact in the outside world. These effects were also being seen in music life. The first gramophone records of Arab music were made in Egypt in the early 20th century. The demand seen for radio broadcasts and musical films led to changes in the tradition of music. Musical films were being transformed from improvisations to written and rehearsed presentations. Singers began singing in front of orchestras, which had combined Western musical instruments with the traditional ones. Some of these mentioned musical pieces in the 1930s were closer to Italian and French café music more than to traditional music. The old styles did also continue to exist with these. Initiatives to examine these existed in Cairo, Tunisia, and Baghdad. Umm Kulthum in particular, who sang poems written by Shawqi and other poets in song form and portrayed the Tarab style with free improvisational competence, gained great repute at this time, and the tools of communication spread her fame to the whole Arab world right from the start.

If we go back to Umm Kulthum again, how was her life story shaped within this general picture? Wasn’t she born and living in the middle of these changes and fractures anyway?

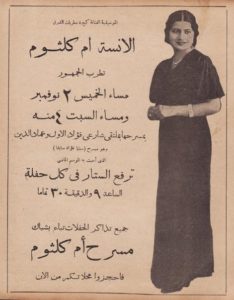

Umm Kulthum’s impressive career was actually also exactly shaped by these transformations. Her life beginning in the poor delta villages at the very start of the century, firstly receiving religious knowledge within traditional education and memorizing the whole Quran at a young age; the features of her story could pass as ordinary for many Egyptians. The great talent she possessed, however, did not escape the attention of first her family and then also the social environment where she lived. Within the highly conservative environment of the early 1900s, a girl singing was not an easy thing to accept. Sheikh Abu al-Ila Muhammad, whom Umm Kulthum had met on her way to Cairo, would be an undeniable contribution in her life, which had been spent going to celebrations like weddings and mawlids in surrounding villages and towns in men’s clothing alongside her father Sheikh Ibrahim, who was the imam in the village where they lived. She learned from him the subtleties of being a singer, of combining the lyrics and music, of breathing techniques, and of pronunciation. Her name was first heard in Cairo’s music life in the early 1920s. In the same period, names like Badia Masabni, Munira al-Mahdiyya, and Fatiya Ahmad, who were especially known for their operatic style of singing, reached quite a large popularity in Cairo’s promenade. Umm Kulthum’s repertoire was originally composed of religious works. After meeting the poet, Ahmad Rami, however, her repertoire evolved into popular song writing based on the mastery of love poems. This musical business union led her to both a great career and a distinguished repertoire. Umm Kulthum right away managed to revive a more traditional music style beyond the musical tendencies of the period. This style is tarab. Tarab in Arabic music can be defined as musical emotion itself or the extraordinary feeling that music arouses, as the moment of becoming ecstatic, or as aesthetic enthusiasm. Vocal techniques of the religious-mystic style, native, and Pan-Ottoman secular contents are contained in the core of tarab performance. While the traditional performance locales popularly were the ferah (wedding entertainment) and sahra (musical evening entertainment), the performance venue in big cities like Cairo, Damascus, Aleppo, and Beirut were cafes.

The style of tarab music, as far as I understand, is an important stopping place in terms of our understanding Umm Kulthum’s musical orientations. How Umm Kulthum uses this style, could it be interpreted as her own original?

One of the original things that Umm Kulthum created is also her own styles of interpretation already. This exists in many areas. While the choice of Umm Kulthum, who undertook the mission to revive the landscape in a neo-classical sense, was evident in Egypt since the 1940s as directed at being part of a strong stream based on the social order of Islam and classical Arab civilization, the way she lyrically and musically caught the most ideal form of classical Arab music had her arrive at a privileged position of not being comparable to any of her contemporaries. The strongest aspect of her singing was her extraordinary talent in free improvisation. Another significant point is her Arabic pronunciation. The clarity of her words and dominance of the language was flawless. Taha Hussein said, “I take great pleasure from her excellent use of Arabic.” According to him, Umm Kulthum’s art was one of word and interpretation that surpassed his talent in singing. Ibn Sureyj, who lived in the 8th century in the classical period of Arab culture, touched upon the use of good pronunciation and Arab case suffixes in his article on the topic of what is expected from a good singer. Umm Kulthum, while providing brilliance by tying the lyrics to the melody, was able to establish an extraordinary dominance of the audience over the subject. These were all the most important points in being able to transfer what was juxtaposed in her musical expression and message.

Speaking of transfer, Umm Kulthum was a person who could also interact well with the audience. Actually, it’s as if so many sectors of fans and the kind regard towards her are a situation also directly related to this form of music.

“Umm Kulthum is the most important player in the disassociation of Pan-Ottoman influences in Egyptian music and the emergence of a native style.”Yes, this is an important issue. When we look in the most general sense, the Arab-Egyptian perception already contained clear patterns regarding Umm Kulthum’s musical creativity. According to these, she was a good singer because “She can read the Quran.” Expressions in the form of “She revives the Arabic couplet anew with her performances,” and “she never sings the lines the same way twice,” are clear indications of her artistic cognitive ability. This situation is revealed clearly in Virginia Danielson’s study on Umm Kulthum. The essence of tarab is the connection of the words with the music in her style. This bond represent the departure from the process of enchantment (tatrib), which is created only through melodic derivations that are based on the Turkish singing style, such as where Arab singers create one of the most perfect examples. Umm Kulthum is the most important player in the disassociation of Pan-Ottoman influences in Egyptian music and the emergence of a native style. The lyrics and melody were able to be more effective through the cadences (kalafat) she used in her interpretations. She improvised the lyrics by using her voice almost like an instrument. In this, her knowledge of zakharif had a great role. These historical vocal ornamentations cover vocal entries a little above or below the note, slip transitions from one sound to another, and situational changes of rhythmic emphasis. Umm Kulthum was recreating parts with trills, mordant-like figures, and tremolo additions. According to Oliver Leaman, who worked on Islamic aesthetics, “Umm Kulthum’s most impressive quality was her mastery of solving and distributing the song’s rhythmic form in order to be able to diversify, replay, and rewrite the complex areas of the song both in terms of the lyrics and music in order to dramatize free improvisations, music, and lyrics. It was certain to have no resemblance in directing the audience like they want. Using the Arabic couplets with their absolute metric measure as lyrics made her job easier. When her reputation became well-spread, she was listened to by millions of people who were aware her ability as a singer was one seen only every few hundred years in the Middle East. Her absolute dominance over the song allowed many composers’ works to be held responsible to her. In this case, her ability to transform the most ordinary material into an extraordinary musical work was effective. She could transform words and music lacking extraordinary qualities into a unique piece of music. This mutual interaction of the Arab public playing the ideal audience role in the open relationship of the singer and audience gave her the courage to reach new heights in her creativity.”

We are talking about a period in Egypt when there was a lot of confusion and political turmoil. If we again return to the conditions of Egypt at the time, how was Umm Kulthum able to be located in a place for that period, or where did these developments stand with her own music?

In the most general sense, Umm Kulthum’s stage experience had already developed around a multi-layered struggle, which you’ve also indicated. In the first period in Cairo while receiving music lessons from masters like Sheikh Abu al-Ila Muhammad, Umm Kulthum at the same time was also found in the assemblies of the elite who held the pulse of sensitive public opinion on national issues. For example, she was witness to the conversations of names like Dr. Taha Hussain and Mansur Fahmi, in the house of the Abd al-Raziqs, a distinguished family of Cairo. These “private networks or groups,” of which a number of families were formed, constituted the center of the other side of the political parties and nationalist debates at the time. The world of Umm Kulthum was colored with the interest that had begun to lightly hear issues of resistance against the local government and foreign sovereignty. At that time, the Great Depression, as well as colony management and local formations’ inability to seize or maintain power, caused the disappointments that had already arisen in Egypt, and these problems became widespread in society. Political issues were among the topics found in the press and alongside music and presentations on the national radio station established in 1934. On a wider scale, interest continued to be seen on the matter of being independent from the foreign authority and brought all these cultural influences together. Objections in the form of “Egypt is the Egyptians” also fueled debates on music politics and the modernization of music. Many headings such as harmony, quarter tones, and orchestration were considered and debated from the perspective of westernization at the Arab Music Conference of 1932 in Cairo, which also involved Umm Kulthum’s performance. In short, while everything in 1930s Egypt was politicized over the phenomenon of independence, cultural institutions were included in the focus of these debates and were interpreted over Western, local, universal, and authentic balances. The ultimatum Britain gave King Faruq in 1942 during World War II and the failures experienced by the army that could not be managed well in the war raised a response among the public directed at England and its collaborators within Egypt. In this context, the romantic escapades of the 1920s and 1930s had failed. Anymore, the Egyptian audience showed interest in works containing concrete reality. In contrast to Ahmad Rami’s romantic poetry, Bayram al-Tunisi’s poetry with its realistic expression was in demand. Umm Kulthum, reading all these orientations correctly, went on to form a repertoire that would address the sentiment of the community more from the experimental songs of Muhammad al-Qasabji, which were based on Rami’s romanticism in the 1940s. After the war, she went in front of the audience with a repertoire based on the partnership of Zakariyya Ahmad and Bayram al-Tunisi with pieces written in a more everyday language. By preparing artistic works reminiscent of small dialogues for Umm Kulthum, al-Tunisi, whose successful works also appeared at the same time on the issue of political satire, included sayings the public often used as were in most of his poetry and statements that would identify with the Egyptians of the working class. Danielson described this process very well. In his compositions, the hero, who identified with Umm Kulthum, was not the type of girl who trembled over the aristocracy; she was the strong and honest type of Egyptian woman who worked. While the populist repertoire that this partnership between composer and performer had unveiled maintained its strength for many years, Umm Kulthum began working with Riyad al-Sunbati, who had also reached a very competent point in the form of the Ottoman couplet alongside song composition. While Riyad al-Sunbati composed couplets from what Ahmad Shawqi had written, his reputation provided Umm Kulthum’s repertoire with neoclassical-style contributions. Besides being a good oud player, she also got a good look at composition. Behind Umm Kulthum’s admiration for al-Sunbati’s couplets, as Danielson also stated, the impact of a strong, deep social and political movement could be seen directed at confirming that Islam and classical Arab civilization are the foundations of social order. Through the poetic texts, Umm Kulthum’s style contained references to the old Arab and Islamic culture. At a time when the response toward both local and international injustice was increasing, this attitude offered a philosophical foundation to a large group. Writing couplets while taking them from classical Arab poetry and making references to Islamic and Arabic history in his artworks, Ahmad Shawqi also defined the idea for the events and contemporary developments that occurred.

In the most general sense, Umm Kulthum’s stage experience had already developed around a multi-layered struggle, which you’ve also indicated. In the first period in Cairo while receiving music lessons from masters like Sheikh Abu al-Ila Muhammad, Umm Kulthum at the same time was also found in the assemblies of the elite who held the pulse of sensitive public opinion on national issues. For example, she was witness to the conversations of names like Dr. Taha Hussain and Mansur Fahmi, in the house of the Abd al-Raziqs, a distinguished family of Cairo. These “private networks or groups,” of which a number of families were formed, constituted the center of the other side of the political parties and nationalist debates at the time. The world of Umm Kulthum was colored with the interest that had begun to lightly hear issues of resistance against the local government and foreign sovereignty. At that time, the Great Depression, as well as colony management and local formations’ inability to seize or maintain power, caused the disappointments that had already arisen in Egypt, and these problems became widespread in society. Political issues were among the topics found in the press and alongside music and presentations on the national radio station established in 1934. On a wider scale, interest continued to be seen on the matter of being independent from the foreign authority and brought all these cultural influences together. Objections in the form of “Egypt is the Egyptians” also fueled debates on music politics and the modernization of music. Many headings such as harmony, quarter tones, and orchestration were considered and debated from the perspective of westernization at the Arab Music Conference of 1932 in Cairo, which also involved Umm Kulthum’s performance. In short, while everything in 1930s Egypt was politicized over the phenomenon of independence, cultural institutions were included in the focus of these debates and were interpreted over Western, local, universal, and authentic balances. The ultimatum Britain gave King Faruq in 1942 during World War II and the failures experienced by the army that could not be managed well in the war raised a response among the public directed at England and its collaborators within Egypt. In this context, the romantic escapades of the 1920s and 1930s had failed. Anymore, the Egyptian audience showed interest in works containing concrete reality. In contrast to Ahmad Rami’s romantic poetry, Bayram al-Tunisi’s poetry with its realistic expression was in demand. Umm Kulthum, reading all these orientations correctly, went on to form a repertoire that would address the sentiment of the community more from the experimental songs of Muhammad al-Qasabji, which were based on Rami’s romanticism in the 1940s. After the war, she went in front of the audience with a repertoire based on the partnership of Zakariyya Ahmad and Bayram al-Tunisi with pieces written in a more everyday language. By preparing artistic works reminiscent of small dialogues for Umm Kulthum, al-Tunisi, whose successful works also appeared at the same time on the issue of political satire, included sayings the public often used as were in most of his poetry and statements that would identify with the Egyptians of the working class. Danielson described this process very well. In his compositions, the hero, who identified with Umm Kulthum, was not the type of girl who trembled over the aristocracy; she was the strong and honest type of Egyptian woman who worked. While the populist repertoire that this partnership between composer and performer had unveiled maintained its strength for many years, Umm Kulthum began working with Riyad al-Sunbati, who had also reached a very competent point in the form of the Ottoman couplet alongside song composition. While Riyad al-Sunbati composed couplets from what Ahmad Shawqi had written, his reputation provided Umm Kulthum’s repertoire with neoclassical-style contributions. Besides being a good oud player, she also got a good look at composition. Behind Umm Kulthum’s admiration for al-Sunbati’s couplets, as Danielson also stated, the impact of a strong, deep social and political movement could be seen directed at confirming that Islam and classical Arab civilization are the foundations of social order. Through the poetic texts, Umm Kulthum’s style contained references to the old Arab and Islamic culture. At a time when the response toward both local and international injustice was increasing, this attitude offered a philosophical foundation to a large group. Writing couplets while taking them from classical Arab poetry and making references to Islamic and Arabic history in his artworks, Ahmad Shawqi also defined the idea for the events and contemporary developments that occurred.

This reflection of the political agenda and language in music, didn’t it also probably find itself in Umm Kulthum?

Didn’t it find? Like we identified at the start, Umm Kulthum’s repertoire was shaped according to the flow of historical processes. Shaping, giving shape, and entering into the mind. For example, one vinyl record had 5 couplets belonging to Umm Kulthum, Shawqi, and al-Sunbati. The lines were able to often cover different topics one by one like history, politics, religion, and love. Lines were included that were transformed into slogans in the language of the pro-independence nationalists in Egypt, even the religious-themed works like Salou Kalbi, Wolida Alhouda, and Nahj al-Burda. Shawqi’s composition, Salou Kalbi, opens with an address to the lover, saying after praising the prophet Muhammad, “Requests are not met by wanting; the world is only won through struggle” in a way that supports the growing national reaction to the British occupation in Egypt and the bad management of King Faruq.

“The couplet named “Sudan” tells of the Egyptian-Sudanese union that became a national issue. In short, the success of the al-Sunbati compositions, which placed classical poetry into new molds, offered Umm Kulthum’s performance creativity new opportunities.”The couplet named “Sudan” tells of the Egyptian-Sudanese union that became a national issue. In short, the success of the al-Sunbati compositions, which placed classical poetry into new molds, offered Umm Kulthum’s performance creativity new opportunities. The unique harmony between the composer and artist, great appreciation in the educated sector that was highly sensitive about its own past, and these works reminded society at the same time of the importance of their cultural heritage and traditional Arab art, as well as the importance of customs for actual living. Additionally, al-Sunbati was able to offer innovations in the field of music without breaking from the Arabic fundamentals of composition. These works were influenced by Abd al-Wahhab’s Western style and represented the neoclassical styles on the side of his modern, broad orchestration-based style and tradition in Arab music. Thanks to her ability to read poetry alone or with melody, Umm Kulthum provided people who had read important examples of Arabic poetry, and even those who had not, to learn and memorize it. Through her preference for Arabs, who have an extremely strong tradition of poetry, she transformed into a master who taught poetry to society. In many comments, the reason her praise grew was in the form of “She gave us back the Qasa’id.” The facts that the repertoire Umm Kulthum formed held the pulse of the community and the musical collaboration she established for this strengthened her influence as well as made her one of the authorities who provoked thought on the topic of cultural policy in the country need to be accepted. When she was nominated for the Musicians Union in 1945, she told the art director of the company Odeon Records, Khalil al-Masri, who cautioned her that this was not a very good decision, that she could serve as a single leader and had ideas that could solve problems. Thus in 1952 at the time when the Free Officers Movement was devoted to the overthrow of King Faruq, Umm Kulthum was at the head of one of the most important cultural identities of Egypt.

Egypt had the Free Officers Coup and afterwards a process leading to Arab Nationalism. Before we forget, in this process we also see the rise of Nasser, who would become a very important figure for the entire Arab world. As a matter of fact, for Arab nationalism. When we look at the developments so far, can we say the interest in Umm Kulthum increased more through the relations of Nasser and the importance of her symbolism had become more apparent?

The importance of symbols increased in the period of trying to develop Arab nationalism as a unifying ideology over the complex sectarian and cultural identities in a broad geography. As Benedict Anderson said, nationalism is based on the concept of a common fate and language. In what Anderson defines with two phenomena like belonging and the imaginary community, to say nation is not to say imaginary or fantastic because this is not just perceived; it is also a community that has us feel. It doesn’t appeal just to awareness; it also appeals to emotions. In other words, nation signifies the awareness and sense of belonging to a community whose members have not met and that is not determined by kinship, common origin, a network of common interests, or common religious belief. Nasser’s Pan-Arabic policy was shaped by a cultural identity. For him, the Arab identity came before the Muslim or Christian identity. In that case, the fact that a common tone, that a cultural symbol that would unite the imagined community over this language was needed, had Umm Kulthum become the most suitable candidate for this role. Umm Kulthum’s respect throughout the Arab world and her identity that exceeded the bounds of music could be affective, and also was just as often as the Egyptian bureaucrats, politicians, or journalists were unable to create. Above all, the Egyptian dialect was recognized and ironed out thanks to her songs. This situation served to accommodate also ironing out the Egyptian political actors’ radio or television speeches. Moreover, Umm Kulthum’s profound commitment to Arabic culture, literature, and history contributed to combining them thanks to this unifying role of hers. In the eyes of all Arabs, she was the representative of the Egyptian identity, way of life, and musical style, but above all else, she was the Arabs’ cultural ambassador in the modern age.  Interpreting tradition as voice provided a bond to be formed between the present and the past. As a matter of fact, Umm Kulthum sang nationally as often as not between 1952 and 1960; when making a numerical statistic, these works formed about 50% of her repertoire for that period. After 1960, the new repertoire covered a third. Songs for celebrating and commemorating were not a new experience in her career. In a concert organized to celebrate the establishment of the Arab League in 1945, Umm Kulthum gave voice to Zakariyya Ahmad’s work, “Zahr al-Rabi.” The Shawqi texts that she had read in the 1940s were mostly accepted as national content. Beyne Ahdeyn [Between Two Eras], first performed in 1949, contained visible nationalistic themes. These songs were made more in the mood of the national march and were performed with wide orchestration that included copper reeds and tympani. In this respect, the mood of the military march was felt in the European style in the songs with national content that were sung by other artists of the period. In Umm Kulthum’s performances, however, an arrangement appropriate to her musical tendency and character drew attention. The works, Waqafa al-Khalq (Mısır Explains Itself, 1951) and Wallahi Zaman Ya Silahi (O My Weapon, It’s Been Awhile, 1956), were held dear by the public; the second one became the Egyptian national anthem. Her reputation brought to the agenda appeals to her for preparing works in this style from other Arab countries. Umm Kulthum, who had prepared two songs for the Kuwait National Holiday and a national anthem for Iraq in the 1960s, also began to share her attitudes more openly with the public towards the current political and social developments of the same years. Supporting reforms and being influenced by Arab independence and the content of the Pan-Arab ideal found her at a common point with wide masses. Nasser’s respect for Umm Kulthum, his personal friendships, and applying her ideas on cultural topics brought together these two important personalities in the eyes of the public on the issue of representatives of one mind and action in politics and art. Umm Kulthum developed friendships with key figures like Abdel Hakim Amer, Jamal Salib, and Muhammad Hasanayn Haykal and, by taking part in the music committees of various ministries, was found in forums where she proposed her ideas on issues like music education, publication, and performance. According to the French writer, Tournier, Umm Kulthum was the soul of Egypt and the whole Arab world in the 1960s. Rumors spread around, “How’s the situation in Egypt? Very beautiful: three days of soccer, three days of Umm Kulthum, and one day of meat, too.” She expressed the common aspirations and passions in a period where the Arab world was shaken from top to bottom. She was not just a voice for Arabs. “Indeed, she regarded herself as the wife of all Arab people, a kind of Madonna, a Vesta priest dedicated to applying her art, which she saw as a national service as much as emotionally her life.” Her voice didn’t just give life to love-themed emotional songs; it spread her thoughts of Arab unity with a lyrical enthusiasm through songs loaded with messages of oneness and unity. Nasser’s blend of classical Arabic with everyday speech was found in Umm Kulthum in a musical sense resembling the strong political rhetoric which is highly effective on the masses. As a Palestinian journalist said, they were seen as the two powerful leaders in the Arab world in the 1950s. In the 1960s, the Palestinian issue, which formed an increasingly intense political agenda, found a response in the music of great artists like Kulthum and Fairuz. This situation also transformed each of these two names into a social phenomenon beyond their powerful musician identities.

Interpreting tradition as voice provided a bond to be formed between the present and the past. As a matter of fact, Umm Kulthum sang nationally as often as not between 1952 and 1960; when making a numerical statistic, these works formed about 50% of her repertoire for that period. After 1960, the new repertoire covered a third. Songs for celebrating and commemorating were not a new experience in her career. In a concert organized to celebrate the establishment of the Arab League in 1945, Umm Kulthum gave voice to Zakariyya Ahmad’s work, “Zahr al-Rabi.” The Shawqi texts that she had read in the 1940s were mostly accepted as national content. Beyne Ahdeyn [Between Two Eras], first performed in 1949, contained visible nationalistic themes. These songs were made more in the mood of the national march and were performed with wide orchestration that included copper reeds and tympani. In this respect, the mood of the military march was felt in the European style in the songs with national content that were sung by other artists of the period. In Umm Kulthum’s performances, however, an arrangement appropriate to her musical tendency and character drew attention. The works, Waqafa al-Khalq (Mısır Explains Itself, 1951) and Wallahi Zaman Ya Silahi (O My Weapon, It’s Been Awhile, 1956), were held dear by the public; the second one became the Egyptian national anthem. Her reputation brought to the agenda appeals to her for preparing works in this style from other Arab countries. Umm Kulthum, who had prepared two songs for the Kuwait National Holiday and a national anthem for Iraq in the 1960s, also began to share her attitudes more openly with the public towards the current political and social developments of the same years. Supporting reforms and being influenced by Arab independence and the content of the Pan-Arab ideal found her at a common point with wide masses. Nasser’s respect for Umm Kulthum, his personal friendships, and applying her ideas on cultural topics brought together these two important personalities in the eyes of the public on the issue of representatives of one mind and action in politics and art. Umm Kulthum developed friendships with key figures like Abdel Hakim Amer, Jamal Salib, and Muhammad Hasanayn Haykal and, by taking part in the music committees of various ministries, was found in forums where she proposed her ideas on issues like music education, publication, and performance. According to the French writer, Tournier, Umm Kulthum was the soul of Egypt and the whole Arab world in the 1960s. Rumors spread around, “How’s the situation in Egypt? Very beautiful: three days of soccer, three days of Umm Kulthum, and one day of meat, too.” She expressed the common aspirations and passions in a period where the Arab world was shaken from top to bottom. She was not just a voice for Arabs. “Indeed, she regarded herself as the wife of all Arab people, a kind of Madonna, a Vesta priest dedicated to applying her art, which she saw as a national service as much as emotionally her life.” Her voice didn’t just give life to love-themed emotional songs; it spread her thoughts of Arab unity with a lyrical enthusiasm through songs loaded with messages of oneness and unity. Nasser’s blend of classical Arabic with everyday speech was found in Umm Kulthum in a musical sense resembling the strong political rhetoric which is highly effective on the masses. As a Palestinian journalist said, they were seen as the two powerful leaders in the Arab world in the 1950s. In the 1960s, the Palestinian issue, which formed an increasingly intense political agenda, found a response in the music of great artists like Kulthum and Fairuz. This situation also transformed each of these two names into a social phenomenon beyond their powerful musician identities.

Like, in this case it also seems possible to talk about the serious effect of the Palestinian issue in general on Umm Kulthum in parallel with the many influences of the 1967 Arab-Israeli War on the Arab world. Of course, the policies Egyptian leader Nasser installed towards these developments and the discourses produced would also form the other part of the picture. Am I wrong?

No, of course not; the results of 1967 Arab-Israeli War have since brought with it great changes for the region. The occupation of East Jerusalem and the loss of Sinai and the Golan heights, as geopolitical weaknesses, have left Arabs faced with a great shame. As a Palestinian has said, “Nasser now resembles a cracked Chinese vase. He will never again resemble his old self.” Umm Kulthum’s music was also used in the campaign started for returning the Egyptian leader, who had resigned after the war, to his duty. Umm Kulthum sang, “Get up and listen to your heart, because I am the people/Stay, you are the protector,” in her song and was found calling in the form, “Stay, you are the love of the nation/The people’s love and blood flow.” From her biography, Umm Kulthum, who was extremely sensitive about the importance Egypt and the Arab world had given to her leadership role, was understood to have been negatively psychologically affected after the 1967 war. Her friends noted she had not met with anyone for days, and had even retreated to the cellar of her house. Within a short time, however, her personal program was seen to come back to life in order to be able to repair Egypt’s shaken prestige. Umm Kulthum showed herself in three stages: dismissing the losses Egypt had reached after the 1967 war, dismissing the frustrations the Arab world had experienced, and attempting to repair the damage. Firstly, her launching a financial aid campaign for her country through her identity as an Egyptian female citizen drew attention. For this, she first donated her jewelry. This gesture of hers was repeated by many wealthy Egyptian women. People anymore were also donating their jewelry when coming to her concerts.

“Umm Kulthum’s music was also used in the campaign started for returning the Egyptian leader, who had resigned after the war, to his duty. Umm Kulthum sang, ‘Get up and listen to your heart, because I am the people/Stay, you are the protector,’ in her song and was found calling in the form, ‘Stay, you are the love of the nation/The people’s love and blood flow.'”On the second point, vinyl records were made drawing forth themes found in the call of oneness, encouraging Egypt and the Arab public. In this perspective, two vinyl records in particular recorded after 1967 give a great echo. Here, national themes and religious terminology immediately have themselves felt. The lyrics wove the theme of ittihat (consolidation) from top to bottom with original phrases or the oneness in the Hadith Al Rouh [Tradition of the Soul], which actually belonged to the great Pakistani poet, Muhammad Iqbal. The effect of the music’s lyrical fiction had an empowering quality. As a matter of fact, there is a short speech at the end of the second half of the record on the quality of identity being able to be established through political movements beyond musical expression. The composer of the poem, translated as Hadith el Rouh into Arabic from Shikwa, belongs to Riyad al-Sunbati, one of the most significant architects of Umm Kulthum’s repertoire. Another work where the Islam and Arab theme was intensely felt was Es-Selasih al-Muqaddasa, again composed by al-Sunbati over the words of Saleh Jawdat. The theme of the work is the forming of the Great Mosque of Mecca, the Prophet’s Mosque of Medina, and Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, Islam’s three sacred cities. The work, in which religious motives are completely processed to the texture of music, was often played on Arab radio stations in a way that would fairly recall the air of the march in the flare-up period of the Palestinian issue. In addition to these, the most effective initiatives she made on behalf of Egypt were the international concerts conducted through her capacity as the official cultural ambassador.

I guess we can say that now Umm Kulthum was at the peak of her reputation at that period. Even so, we can mention a celebrity who wasn’t just within the Arab world; she also spilled over beyond its borders.

Of course, in one direction this is true. Olympia, the famous concert hall in Paris where a concert was performed in November 1967, was a favor of interest that had been unseen up to that day. When it was heard that the legend of Arab music would give a concert in the capital of France in Edith Piaf’s country, that her earnings from this would be used for Egypt was also disclosed. Bruno Coquatrix, Olympia’s art director, made the invitation to Umm Kulthum at the proposal of the president, Charles de Gaulle. Before this thought of De Gaulle’s, a good start for the development of French-Egyptian relations could not have been. However, both names also experienced a great panic when the concert tickets did not see the same interest. A concert taking place in an empty hall would not be able to have an effect. An alert made in this environment of panic relieved the discomforts. According to this, the Arabs did not like to reserve in advance, so when the day of the concert came, the streets were filled and overflowed. Indeed it was just as expected, and Umm Kulthum’s concerts were not just Parisians; the listeners who came from all over the Arab world realized great success with their intense interest. El-Naggar, the Egyptian ambassador in Paris, told of this success in the report he sent to Cairo. The first foreign concert performed after the 1967 Arab-Israeli War would be her only concert in a Western country. Alongside this, Umm Kulthum’s travels earned the status of official visit with the diplomatic passport issued by the Egyptian government in 1968. Visits occurred with the highest protocol; included in the program were local events in the places gone to, visits to historical and cultural sites, and receptions given by the heads of state in honor of the artist. Umm Kulthum anymore was seen accepted as the voice and face of Egypt in the entire Arab world. A newspaper article clearly reflected the way these concerts were received, singing about love and talking about collecting money for the war. When 1970 arrived, concerts were performed in Tunisia, Libya, Morocco, Lebanon, Sudan, and Kuwait; $520,000 was collected outside of Egypt, $1,202,900 from provincial concerts, and $52,200 from jewelry donated by women. Umm Kulthum, who also gave concerts in Iraq, Bahrain, Abu Dhabi, and Pakistan, had helped the state with a total of $2,530,000, mostly in gold and foreign currency, thanks to these concerts. The important thing here is not the number of course. She also was able to give this money from the fortune she possessed. However, by using all her prestige and artistic charisma, she attempted to raise Egypt’s shattered honor in the Arab public. Preparing a special repertoire and making new songs for each country she visited was a conscious choice such that, even if her lyrics did not involve patriotism, a sense of nationalism was aroused when they were sung by Umm Kulthum. For example, the words “Give me liberty and unclasp my hands” in the song El Atlal (The Ruins), which belonged to Riyad al-Sunbati, and this work were met with great enthusiasm wherever they went and were performed. Among the significant poets whose poems were made into songs were al-Hadi Adam from Sudan, Jurj Jiraq from Lebanon, Muhammad Iqbal from Pakistan, and Nizar Wabbani from Syria. Through these efforts, she saw great respect among the people. Concert tours, which had formed a major breakthrough for a career that extended her identity from a great artist to a legend, provided Umm Kulthum titles in the Arab public like the mother of Arabs (Ummu’l Arab). As these concerts were especially supported through the Egyptian government, Umm Kulthum’s fame and reputation were used for finding support anew among the Arab peoples. When she died on February 3, 1975, the manifestation of great respect undoubtedly was felt for her legendary identity, which had been constructed through conscious choices of the highest degree; the news was announced to the Arab world by reading the Quran over the radio with the greatest respect, as was done for presidents in accordance with Egypt’s official protocol, and 4.5 million people participated in the most crowded funeral to date in the Middle East.

Of course, in one direction this is true. Olympia, the famous concert hall in Paris where a concert was performed in November 1967, was a favor of interest that had been unseen up to that day. When it was heard that the legend of Arab music would give a concert in the capital of France in Edith Piaf’s country, that her earnings from this would be used for Egypt was also disclosed. Bruno Coquatrix, Olympia’s art director, made the invitation to Umm Kulthum at the proposal of the president, Charles de Gaulle. Before this thought of De Gaulle’s, a good start for the development of French-Egyptian relations could not have been. However, both names also experienced a great panic when the concert tickets did not see the same interest. A concert taking place in an empty hall would not be able to have an effect. An alert made in this environment of panic relieved the discomforts. According to this, the Arabs did not like to reserve in advance, so when the day of the concert came, the streets were filled and overflowed. Indeed it was just as expected, and Umm Kulthum’s concerts were not just Parisians; the listeners who came from all over the Arab world realized great success with their intense interest. El-Naggar, the Egyptian ambassador in Paris, told of this success in the report he sent to Cairo. The first foreign concert performed after the 1967 Arab-Israeli War would be her only concert in a Western country. Alongside this, Umm Kulthum’s travels earned the status of official visit with the diplomatic passport issued by the Egyptian government in 1968. Visits occurred with the highest protocol; included in the program were local events in the places gone to, visits to historical and cultural sites, and receptions given by the heads of state in honor of the artist. Umm Kulthum anymore was seen accepted as the voice and face of Egypt in the entire Arab world. A newspaper article clearly reflected the way these concerts were received, singing about love and talking about collecting money for the war. When 1970 arrived, concerts were performed in Tunisia, Libya, Morocco, Lebanon, Sudan, and Kuwait; $520,000 was collected outside of Egypt, $1,202,900 from provincial concerts, and $52,200 from jewelry donated by women. Umm Kulthum, who also gave concerts in Iraq, Bahrain, Abu Dhabi, and Pakistan, had helped the state with a total of $2,530,000, mostly in gold and foreign currency, thanks to these concerts. The important thing here is not the number of course. She also was able to give this money from the fortune she possessed. However, by using all her prestige and artistic charisma, she attempted to raise Egypt’s shattered honor in the Arab public. Preparing a special repertoire and making new songs for each country she visited was a conscious choice such that, even if her lyrics did not involve patriotism, a sense of nationalism was aroused when they were sung by Umm Kulthum. For example, the words “Give me liberty and unclasp my hands” in the song El Atlal (The Ruins), which belonged to Riyad al-Sunbati, and this work were met with great enthusiasm wherever they went and were performed. Among the significant poets whose poems were made into songs were al-Hadi Adam from Sudan, Jurj Jiraq from Lebanon, Muhammad Iqbal from Pakistan, and Nizar Wabbani from Syria. Through these efforts, she saw great respect among the people. Concert tours, which had formed a major breakthrough for a career that extended her identity from a great artist to a legend, provided Umm Kulthum titles in the Arab public like the mother of Arabs (Ummu’l Arab). As these concerts were especially supported through the Egyptian government, Umm Kulthum’s fame and reputation were used for finding support anew among the Arab peoples. When she died on February 3, 1975, the manifestation of great respect undoubtedly was felt for her legendary identity, which had been constructed through conscious choices of the highest degree; the news was announced to the Arab world by reading the Quran over the radio with the greatest respect, as was done for presidents in accordance with Egypt’s official protocol, and 4.5 million people participated in the most crowded funeral to date in the Middle East.

Mustn’t your portrait also be the bearing on Turkey? If we say, what are the reflections in Turkey of Umm Kulthum, who had great respect in the eyes of the whole Middle East and stamped the hallmark of Arab music’s modern period with her music…

From the 1930s onward, Umm Kulthum had also been followed in cities in Turkey, especially in the southeast, just like in neighboring countries. In my conversation with the master, Necdet Yaşar, he said a great admiration for the art and voice of Umm Kulthum had been felt in Antep in his childhood years. In 1939, journalists asked Neyzen Tevfik, who had gone to Egypt, about his opinions on the musicians there upon his return; he responded by saying, “If the whole Orient were to unite, it could not remove an Umm Kulthum.” During the years of World War II, the musical films in which Umm Kulthum played gathered great interest in the cinemas of Turkey. In fact, because of the interest shown, the Press Information Administration of the time made a decision, and playing these films with Turkish overdubs was designated as a necessity. Interestingly, Umm Kulthum was identified as the Star of the Orient, the actress of the big screen, and the lyrical songs that were read were of the famous Turkish singers of the period. This situation caused the birth of a music sector in Turkey based on the adaptation. According to some comments, the impact of this period in Turkey exists in the roots of Arabesque music. However, this is an issue open to debate. We can also say Umm Kulthum became a unique phenomenon over the vocal artists in Turkey. Statements are encountered in the memoirs of names like Safiye Ayla, Münir Nurettin, Perihan Altındağ, and Zeki Müren that contain admiration toward Umm Kulthum. However, even though her voice arrived through her films and records, as well as through Cairo radio, she did not give a concert in Turkey. One can see the effects of Umm Kulthum and Muhammad Abd al-Wahhab degenerated in the Arabesque style that became popular from the 1960s onward. Without sometimes mentioning the names of the composers of many works, another necessary point is the making of records with Turkish lyrics and arrangements, focusing on the singing through various artists.

Lastly, if we must summarize…

Umm Kulthum earned an unshakable reputation by revising her traditional Arab songwriting at a period when, but for the colonial influences and the result of cultural exchanges, the Arab world had surrendered to modern trends. She presented songs that belonged to the Egyptians’ and Arabs’ own cultures that had not been copied from others. In the words of Danielson, it brought her respect and manners unique to Egyptian women in this position, where a musician could be marginalized socially. Umm Kulthum, even if she had not been a political personality, performed her art at a time when politics in the Arab world were very active and shaped by nationalist influences. She surprisingly never avoided expressing the pride she felt for Egyptian culture in a process where most people were able to criticize the old customs and traditions. According to Philip V. Bohlman, who pointed out Umm Kulthum’s place in world music, the world that was recalled by the songs of this great artist, who had the paradoxes of fame and symbolism, were not primarily global; it was local, and even if it carried many forms and meanings, it was concrete and personal in the lives of the listeners worldwide. At the same moment it was both individual and shared. It both made the aesthetic resonance of the religious songs real in the current moment and also created new political and ideological potentials for tradition in a changing world. By this means, Umm Kulthum, who had an important place in world music, “also transformed the technique of world music and of an ‘ethos’ level into affirmations toward women, toward modern Egypt, and toward the Muslim world.” When looked at individually, the achievements of Umm Kulthum made her one of the unique actors of Arab cultural life. Quite beyond her concerts being musical performances, they were a sign of broad cultural influence that transformed into national ceremonies representing unification in the Arab world and its coming together. Her voice represented not just the past, but also the present. When considering her performances were broadly shared in the Arab community and counted among its significant cultural products, she clearly is seen to have cherished a golden age in Arab music through her neoclassical manner. Her repertoire, which was particularly identified with her Arab and Islamic cultural heritage, gained a content that expressed the political issues, defeats, victories, and hopes of the 1960s. Her performances were able to actuate cultural alliance and common values with the audience. She had the position of also culturally being the transmitter of Egypt’s identity through her works and presentation style, such a respectable place for a person in the public sphere of society. Umm Kulthum continues to truly exist today as a legendary identity in the museums in Cairo where her fans visit, on the Arab radio and television stations, in the concert programs that always keep her memory alive, in the various districts of Cairo, in the everyday life of Egypt through her statues of various designs, and in modern times where legends have become null and void.

*This interview was translated into English by Abdullah Kevin Collins.